Researchers have found that trees and soil are even better allies to humanity during the climate crisis than previously thought, especially in urban areas.

The finding could make urban forests more cost-effective for city planners, which could result in more forested areas in cities.

Boston University researchers found that trees growing on the outer edge of a forest grow faster and differently than trees in the interior of a forest, increasing the amount of carbon dioxide it can store.

The scientists also found that forest edge soil in urban areas can store more carbon dioxide than soil in rural areas.

The findings have led the scientists to conclude that the carbon emissions being taken in by forests, known as terrestrial climate sink, are significantly underestimated but could diminish as the effects of climate change worsen.

“We’re not feeling the full effects of climate change because of terrestrial climate sink. These forests are doing an incredible service to our planet,” said Boston University biogeochemist and ecologist Lucy Hutyra.

Scientists currently believe that about 30% of carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels are being taken in by forests, but the real amount may be larger.

Hutyra says her team’s research into forest fragmentation, the cutting up of large forests into smaller patches for development, led to the team’s findings.

In one study, the team used data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Inventory and Analysis program to look at the growth of 48,000 forest plots in the northeastern U.S. The team found that trees on the edges grew nearly twice as fast as those in the forest interior, increasing the potential for terrestrial carbon sink.

A second study looked at the soils at forest edges, finding a major difference between soil in rural and urban areas.

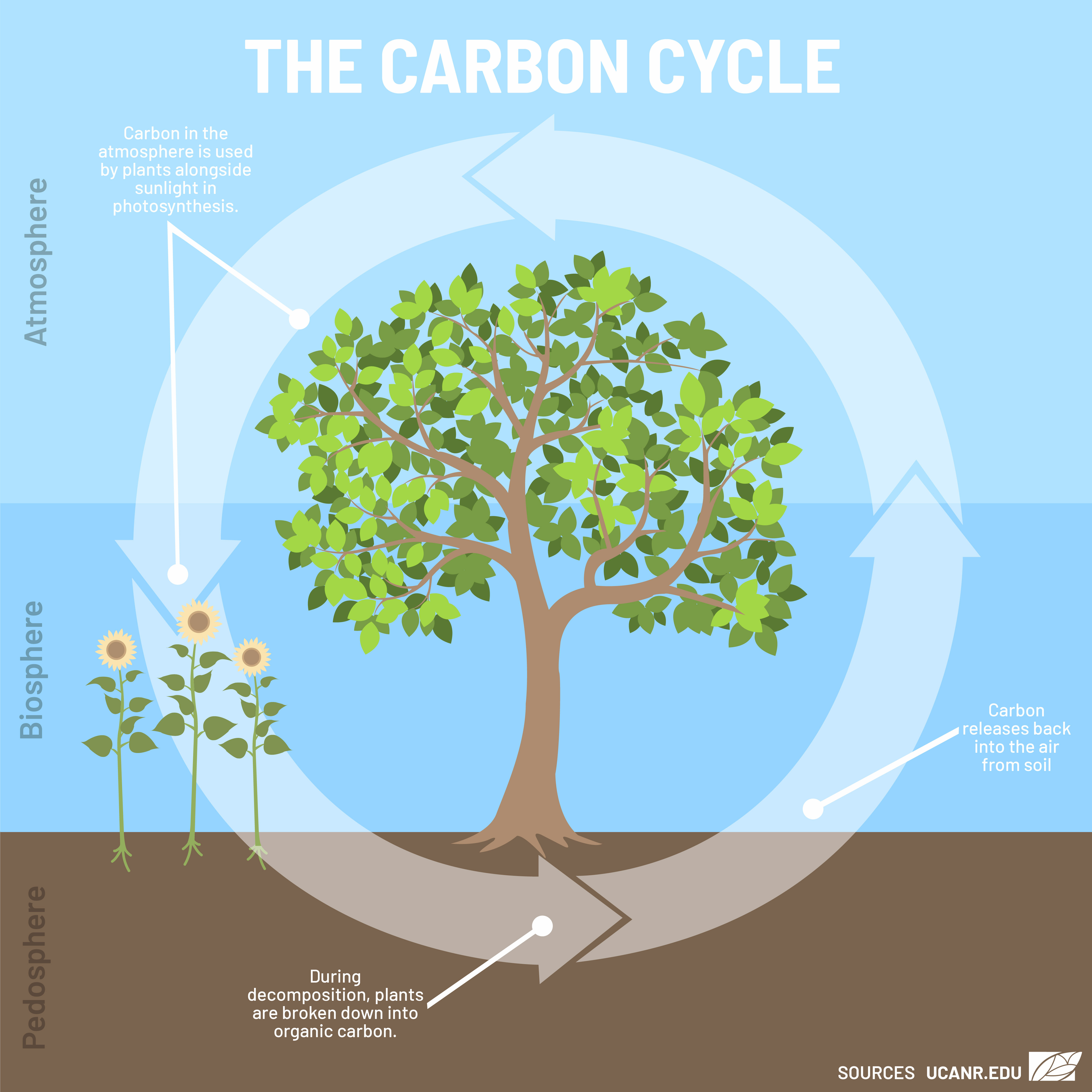

In rural areas, warmer temperatures at the forest edge caused microorganisms to work harder at decomposing leaves and organic matter, causing more carbon dioxide release than in the forest interior.

In urban areas, the soils at the forest edge stopped releasing as much carbon.

“It’s so hot and dry that the microbes are not happy, and they’re not doing their thing,” Hutyra said.

The findings led the researchers to call for a reassessment of the conservation value of forest fragments.

The findings, and the potential added value for urban forests, may have implications for how community leaders invest in urban forests.

Groups like the Indiana Forest Alliance have attempted to persuade Indianapolis city leaders to take action to protect the city’s urban forests, which provide stormwater control, filter air pollution, reduce heat and provide many other services that would otherwise cost the city millions of taxpayer dollars to replicate.

The group introduced its “Forests for Indy Urban Forest Protection Strategy” for the city’s 59 square miles of urban forests at a meeting of the city-county council’s Environmental Sustainability Committee Feb. 28.

“The choices we make now about development will impact the ability of this green infrastructure to provide the environmental, social and ecological benefits Indianapolis needs today and tomorrow,” said Jeff Stant, executive director of the Indiana Forest Alliance. “Protecting these forests will create an insurance policy against climate impacts, expand recreational opportunities and afford access to green space across Indianapolis.”

According to the IFA, 9 square miles of forested land is within city property and protected by city ordinances. The remaining 50 square miles are privately owned and at risk for development. That would leave the city on the hook for the nearly $258 million it would cost to replicate the functions of the trees lost to development.

The committee will meet again in April to discuss how the city could finance the protection of existing urban forests and the planting of new ones.